Around the end of December 2019, Chinese health officials found a cluster of pneumonia in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province. Shortly later, Chinese scientists discovered a previously unknown beta-coronavirus as the likely cause of the illness. SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been renamed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). COVID-19, like the 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic before it, illustrates the catastrophic effect on a vulnerable “naive” population of an emerging zoonotic disease.

What Is Covid-19 Disease?

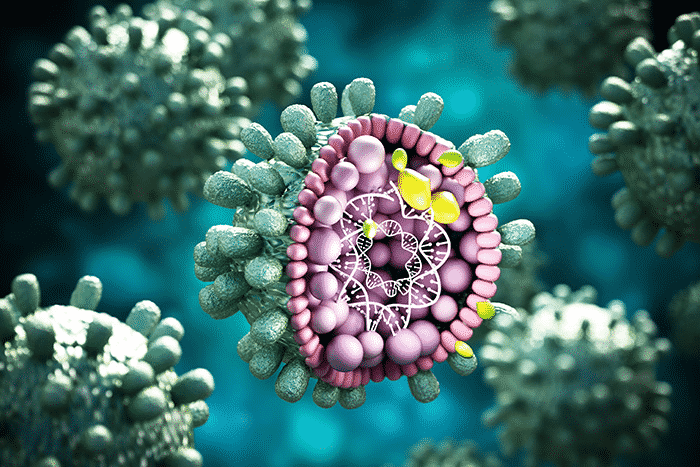

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Case Reports according to the World Health Organization indicate that most patients infected will develop mild to severe respiratory infection but will recover without particular treatment. However, some will become gravely ill and require medical care. People over the age of 65 and those with health problems like heart disease, diabetes, chronic lung disease, or cancer are more likely to get severe covid-19. COVID-19 can cause serious illness and death in people of any age.

When an infected person coughs, sneezes, speaks, sings, or breathes, small liquid particles can be expelled from their mouth or nose and transmit the virus. The size of these particles ranges from large respiratory droplets to minute aerosols.

Researchers have evaluated the size and content characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 particles. Upon analysis of negative-stained SARS-CoV-2 articles by electron microscopy, researchers have had varying results, but the diameter of the virus has been found to range between 50 nm to 140 nm.

Covid-19 And Emergence of Co-Infections

In a pandemic age, the existing prevalence of Covid-19 guarantees co-infections with a multitude of co-pathogens. Hospitalized patients with Covid-19 and other viral respiratory infections are known to be predisposed to bacterial co-infections for an extended length of time. These co-infections result in a poorer prognosis than each infection alone.

With the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, there are various subtleties in epidemiology, microorganism, and clinical symptoms. With more focus on therapy and treatment for multidrug resistant viruses, there has been less focus on understanding how these viruses affect other diseases that people may have. With severe or long-lasting viral infections, several pathogens are sure to complicate the clinical presentation, operational condition, diagnostics, and monitoring.

Co-Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Virus

Since the pandemic, there have been few reports of interactions between influenza and COVID-19. Proper review and meta-analysis reports have revealed the severity of infection in individuals co-infected with influenza and SARS-CoV-2 and the remarkably mild symptoms of co-infected outpatients.

Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus, coupled with a varied clinical prognosis, offers a more significant threat to public health. It has been shown that having both SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A infections makes the disease more severe. This may be because the two viruses enhance each other’s effects.

Previous systematic review and meta-analysis has linked influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and adenoviruses to COVID-19 patients. Co-infections with bacteria and viruses are more common in mild, moderate, and severe diseases leading to weakened immune systems.

Hypertension, diabetes, chronic renal disease, and heart failure have been linked to increased COVID-19 disease severity in individuals with COVID-19 with weak immune response. Pneumococcus plays a significant role in developing lower respiratory tract infections in children with COVID infection.

In those infected with SARS-CoV-2, there is a strong link between Pneumonia specific to Covid-19 disease (14.4%), cardiovascular disease, hypertension (18.6%), and diabetes (11.9%).

Due to the worldwide nature of the pandemic, even non-viral ailments can co-infect. During flu season, the relationship between influenza viruses and SARS-CoV-2 in co-infection has varied given no proper care guidelines. Fewer than 10% of COVID-19 patients had also been infected with another high-risk respiratory virus.

It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 infections exacerbate parasite illnesses.

However, intestinal parasite co-infection was linked to COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 has co-infected several systemic viruses. This co-infection was especially significant in chronic HIV infection when immunosuppression or increased infection susceptibility can make either condition worse. Co-infection with HIV-1 alters T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2, as has co-infection with Mycobacterium TB.

Early-stage COVID-19 illness is linked with frequent bacterial co-infections and severe morbidity and mortality rate.

Co-Infection with Respiratory Pathogens

1.Tuberculosis

There have been instances of COVID-19 co-infection with other respiratory diseases, which may be more prevalent in certain places than others. The initial disease is Tuberculosis (TB). All COVID-19-infected individuals should be screened for tuberculosis, although bigger investigations are required to validate the findings.

Because TB is chronic and COVID is acute, the co-infection may be coincidental, but the high death rate may be larger than for COVID alone.

2.Fungi

Reports have documented cases of coronavirus disease 2019 associated with Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia, either simultaneously or within a few days of each diagnosis. This presents a diagnostic conundrum, especially in people living with HIV who are not routinely tested for and in those with other fungal infections.

Other evidence suggests viral infections worsen or cause fungal infections. When antimicrobials, corticosteroids, or immunomodulating medications are administered, it is not surprising that COVID-19 is related with opportunistic fungi such as yeast and Aspergillus spp.

3.Measles

As well as the relationship between dengue with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a frontline healthcare worker, measles has also been linked as bacterial co-pathogens to SARS-CoV-2 disease. Due to their immunosuppressive impact, Helminthic co-infection may increase morbidity and mortality among COVID-19 patients.

The Effect of COVID-19 on Post-Onset Bacterial Infections Associated with COVID-19

Upper respiratory infections caused by viruses are frequently accompanied by an increase in the number of secondary infections like Commensal Bacteria. In viral-induced inflammation, this elevates the risk of middle ear, sinus, and respiratory infections. The frequency of subsequent infections can be anticipated.

Increased hospitalisation, lengthier ICU stays, and death has been associated with comorbidities. Finally, a large body of research case series suggests that viral infections increase patients’ risk of bacterial co-infections.

Early COVID-19 lung infection has a modest rate of authentic co-infections, as currently understood. This disturbance was seen during the COVID-19 outbreak, according to molecular epidemiology. Respiratory, bloodstream and fungal skin infections are common nosocomial diseases. Empiric, powerful, or extended antibiotics enhance nosocomial infection risk.

During the duration of COVID-19, the kind of recommended co-pathogen develops. In the early stages of the condition, respiratory infections are frequent. As the viral illness progresses, nosocomial diseases may become widespread, notwithstanding the varying institutional rate.

Bacterial co-infections rise with patient ageing. Co-infections are more common in patients with greater comorbidities. Gram-negative bacillus infections are linked to longer hospital stays and severe COVID-19.

COVID-19 co-infecting bacteria include Mycoplasma pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenzae, and Chlamydia pneumonia.

Underlying Issues of Undetected Co-Infections In COVID-19 Patients

Undiagnosed COVID-19 co-infections can cause greater hospitalisation, several treatment options, and even mortality. During pandemics, clin infect dis can lead to underreporting of additional infections that contribute to disease severity.

Progression of upper and lower respiratory viral infections is widely recognised. They may be asymptomatic or suffer for weeks or months. Viruses are usually gone within 10 days of infection. Inflammatory residual or structural damage caused by a virus can cause prolonged sickness.

This might last a few days or months. Although, permanent airway damage and respiratory infection aren’t the same. Co-infection is possible during acute viral excretion and once illness leftovers are apparent. In such a case, it suggests that two viruses are infected at the same time.

The Medicinal Aspect – Antibiotic Resistance

It is crucial to determine if individuals with COVID-19 also have secondary bacterial infections, and if so, if they require antibiotics immediately. This is because antibiotic overuse can lead to the development of drug-resistant bacteria and fungi, which is wished to be prevented.

Antimicrobials may be used as “repurposed medications” to treat the COVID infection itself, even in the absence of co-infection, if antibiotics are frequently used, which is quite prevalent. Antimicrobial resistance can be reduced through social distance, using facemasks and frequent handwashing, isolating sick patients, and sterilising their environment.

56.6 % (965/1705) of hospitalised COVID-19 patients received early empiric antibiotic treatment, but only 3.5 % (59/1705) of hospitalised COVID-19 patients had a proven community-onset bacterial co-infection.

Antibiotic use is a risk factor for co-infection with Clostridioides difficile, and COVID-19 appears to be immune to it.

Concluding Remarks

Early COVID-19 has a low incidence of new genuine viral co-infections. Reports of significant co-infection rates in current diagnostic procedures must be tempered by limitations. COVID-19 will always be superimposed on existing illnesses, and due to the prevalence of COVID-19, various superimposed disorders will emerge during a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Opportunistic and nosocomial infections will occur more frequently in patients with severe COVID-19 due to the long-term nature of some illnesses and the regular use of antibiotics and immunomodulatory therapies. More evidence is required, and greater understanding of COVID-19 co-infections will give better direction for successful antimicrobial therapy for SARS-CoV-2 or genuine co-infections.

We provide a variety of INACTIVATED and LIVE ORGANISMS in a variety of forms such as PURIFIED VIRUSES, INACTIVATED CULTURE FLUIDS. Our bacterial strain collection is available as PURIFIED DNA (or NATtrol), designed to meet your research and product development needs.

Visit the Helvetica Health Care Website for more information.